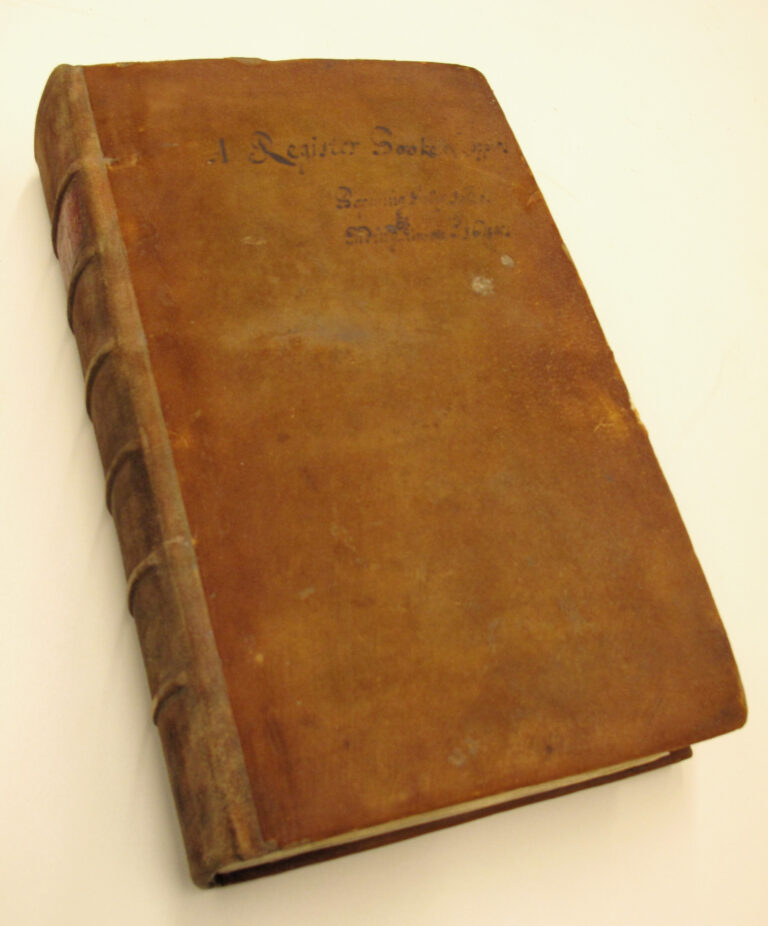

When I started working at the Stationers’ Company in 2017, the first record I saw was the entry in the Stationers’ Register for Shakespeare’s First Folio. The outgoing archivist was giving me the usual sort of handover: which material is most frequently consulted, what are the conservation priorities, how big is the cataloguing backlog, where are the teabags kept… And then she paused to show me this one particular document, traditionally considered by the Stationers to be the treasure of their Archive: you can tell by the fading of the ink, several shades lighter than on the adjacent pages, due to that opening having been displayed at Stationers’ Hall for months on end. The collateral damage has limited how long we’ll ever be able to exhibit those pages again, she warned me, as she slipped the volume out of its custom-built conservation case.

Archivists have a fundamental distrust of the ‘greatest hits’ approach to our collections. Unlike museum pieces, archival documents are connected, contextual beings. Like fungi or honeybees, they derive meaning and sustenance as part of a network of interrelated records: even the most luminous of them loses lustre once it is plucked from its cohort. And so, regardless of my own interest in the history of the record, I was predisposed to a certain cynicism regarding ‘the Stationers’ favourite record’.

Indeed, at first glance, these few lines seem little enough: they are not the texts themselves, not Shakespeare’s own words; indeed Shakespeare’s hand, signature or mark are nowhere to be found in any of the several Registry records of his works entered during his lifetime. The First Folio entry, is, after all, just another transactional record. But what a transaction, and what a record. Each time I see it – or, better still, get to share it – I’m just a little more overawed by the directness of its connection to a long-vanished past. This is the paper they touched. These are the words they wrote. Unlike ink, some magic never fades.

Let’s look at how the entry came about. The Stationers’ Company was a relative upstart on the London Livery Company scene, only receiving its royal charter in 1557 (to put this into perspective, the earliest surviving charter was granted to the Weavers’ Company in 1155). In 1515, the Lord Mayor of London, hoping to put an end to inter-livery bickering, established a ranking of precedence of the 48 companies then in existence. The Stationers weighed in at number 47. So you might expect the Company to recede quietly into those arcane recesses of history popularly associated with fusty academics and historical re-enactment societies. Not so. Because as luck would have it, among the trades and technologies under the Stationers’ control was one which proved to be the major innovation of its day: the printing-press.

Suddenly ideas could be circulated, contested, and reformulated at an unprecedented speed and scale, and the authorities were quick to realise the threat this posed. Successive monarchs issued ordinances and decrees restricting what could be printed, and by whom. To quell the spread of texts deemed, in the words of Elizabeth’s 1559 injunction, ‘heretical, seditious, or unseemly for Christian ears’, licensing by representatives of the Crown and the Established Church was made a prerequisite for lawful printing. And who better to enforce this regulation than an up-and-coming trade association eager to promote and protect its own members?

Granting the Stationers a charter offered an efficient way to monitor the production and dissemination of the printed word. According to the charter, only members of the Stationers’ Company were allowed to print. Moreover, the Master and Wardens of the Company were given the right to search the premises of ‘any printer, binder or bookseller whatever within our kingdom of England or the dominions of the same’ for unauthorised presses and printing material, and to destroy or confiscate such contraband. Only two other livery companies, the Goldsmiths and the Pewterers, held equal rights of search and seizure. If anyone was printing anything that was not officially sanctioned, the Stationers – and, thereby, the government – would know.

For the Stationers themselves, the priority was to secure their own commercial interests, and the Stationers’ Register did just that. An adjunct rather than an alternative to the licensing process (which remained very firmly the province of Church and State), what the Register recorded was the exclusive right of a publisher to print and distribute a particular work. According to the Company’s own internal regulations, before publishing a text, a Stationer was required to visit Stationers’ Hall and seek permission from the Company’s senior officers, who (for a fee) would check that the title hadn’t already been entered to another member. It is this procedure which is referred to in the wording of the First Folio entry:

‘Entred for their Copie vnder the hands of Master Doctor Worrall and Master Cole warden Master William Shakspeers Comedyes Histories, and Tragedyes soe manie of the Said Copies as are not formerly Entred to other men’

This procedure, also, which generated for the lead publishers, Edward Blount and the Jaggards, the monumental task of tracking down those ‘other men’ to whom the unlisted plays had been ‘formerly entered’, through a chain of sales and re-assignments chronicled in the volumes of the Stationer’s Register. From Burby to Ling, Ling to Smethwick, Busby to Johnson, Roberts to Ling, the titles criss-cross a network of deals and disputes, of failing fortunes and botched deceptions, each entry and re-entry embodying a human drama of its own. Dramas which could spill over into subsequent negotiations over inclusion in the Folio compendium: printing was halted, the order of plays was re-arranged, and the publishing consortium acquired two new members.

It’s easy to forget this behind-the-scenes labour in the excitement of encountering, together for the first time, titles such as Macbeth, As You Like It, The Tempest – plays which have structured the stories we tell ourselves ever since they ignited our communal imagination. Yet without that labour, it’s unlikely that we’d still have those texts, or even remember their names. Of all the plays performed upon the English stage during the golden age of the English Renaissance, only a fraction were printed; and only a fraction of those would have found their way into the Stationers’ Register.

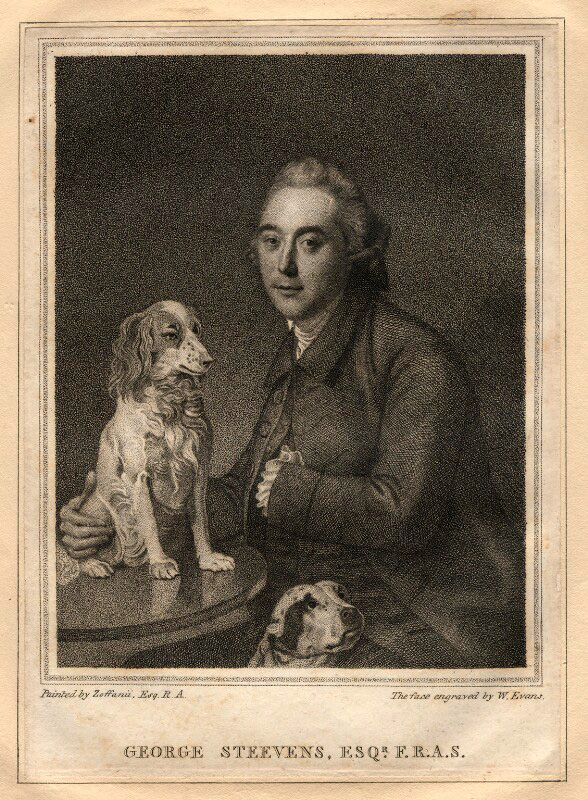

A reminder that archives, like the memories they embalm and the histories they birth, are fickle things. On this page of the Stationers’ Register, only one Jaggard, Isaac, is entered, with Edward Blount, as a proprietor of the First Folio texts. By the time the entry was made, his father William was three months’ dead. And ironically, with all the players in this particular drama – the eulogised author, the loyal editors, the enterprising publishers – the only signatory mark on the entry was made by a complete interloper, over a century later. An asterisk cresting the initials ‘G S’, this is the emblem of George Steevens, the gifted, idiosyncratic scholar who completed Samuel Johnson’s edition of Shakespeare.

Independently wealthy (his father’s portfolio included a seat as a director of the East India Company), Steevens’ editorial reputation has been overshadowed by his penchant for elaborate pranks: on one occasion he had some Anglo-Saxon words etched with acid onto a block of marble, put about a story that the tombstone of Hardecanute had been recently dug up in Kennington Lane, and waited until a well-known scholar had presented a paper on it to the Society of Antiquaries before revealing the hoax. Unaware of, or indifferent to, this streak of mischief, the eighteenth-century Stationers allowed Steevens full access to the Registers, a trust which he characteristically abused. As exuberant and idiosyncratic as the double ‘e’ in his name, this configuration of asterisk and initials marks every entry related to Shakespeare, like a graffiti tag declaring to posterity that George Steevens, too, was here.

Dr. Ruth Frendo

14th September 2022