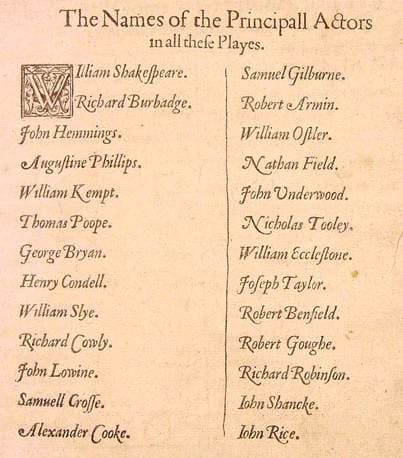

The 1623 First Folio is famously the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays, and the earliest printed source we have for a number of his dramatic works. Less well-known is the fact that the 1623 text also preserves one of the most comprehensive lists of the actors who originally performed in his plays.

The First Folio’s list of ‘the Principall Actors in all these Playes’ names twenty-six men and boys. This includes Shakespeare, whose name appears first, in pride of place, as well as John Heminges (1566-1630) and Henry Condell (fl. 1598-1627)—the company fellows who oversaw the publication of the First Folio—William Kemp (fl. 1585-1602), the company’s first clown, famous for his jigs and improvisation and the originator of comic roles such as Dogberry (Much Ado About Nothing) and Bottom (Midsummer Night’s Dream), and Kemp’s replacement as company fool, Robert Armin (c.1567-1615), for whom Shakespeare wrote roles such as Feste (Twelfth Night) and the Fool in King Lear.

The list of actors also includes early company members from the days of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (1594-1603), such as Augustine Phillips (fl. 1590-1605), Thomas Pope (fl. 1586-1603), George Bryan (fl. 1586-96), William Sly (fl. 1590-1608), and Richard Cowley (fl. 1593-1619), as well as later adult members of the King’s Men such as Nathan Field (1587-1620), Joseph Taylor (1586?-1652), Robert Benfield (c. 1583-1649), John Lowin (1576-1653), William Ostler (c. 1588-1614) and John Shank (c. 1570-1636). Others named in the list are known to have joined the Shakespeare company as boy apprentices, including Alexander Cooke (c. 1583/4-1614), Nicholas Tooley (fl. 1603-23), John Rice (1590?-1630>) and Richard Robinson (c. 1596-1648).

Little is known about some of the individuals named as actors in the First Folio—such as Samuel Crosse—but others are better documented; none more so than the man whose name appears immediately after Shakespeare’s and to whom Shakespeare left money to buy a mourning ring in his will, along with Heminges and Condell—Richard Burbage (1568-1619).

Famed as a ‘delightful Proteus’ who ‘wholly’ transformed ‘himself’ into the parts he played, Richard Burbage was not only a leading sharer in Shakespeare’s acting company and one of England’s first theatre entrepreneurs, as joint owner of the Globe and the Blackfriars theatres, he was also one of England’s first ‘star’ actors. Key to this fame were the Shakespearean tragic roles he played with the Lord Chamberlain’s (later the King’s) company from 1594 until his death in 1619, starting with his first signature role as Shakespeare’s charismatic and wickedly witty anti-hero, Richard III.

Burbage may not have been Shakespeare’s first Richard III, but he made the role his own, multiple contemporary allusions identifying him with the ‘crookback’ king and pointing to the impact of his performance in the part on audiences of the day. These allusions include John Manningham’s bawdy 1602 anecdote about a play-going woman who is reported to have arranged a secret night-time assignation with Burbage after seeing him as Richard III, and a joke in a poem by Richard Corbet about an inn host who inadvertently conflated Burbage and Richard during an account of the Battle of Bosworth, ‘For when he would have said, King Richard dy’d / And call’d a Horse, a Horse, he Burbage cry’d’. As Alexander Leggatt observes, this anecdote highlights how ‘for his generation’ Burbage did not simply act Richard, he ‘was Richard III’.

Shakespeare’s play about Richard’s downfall is conventionally defined as a history play but its protagonist has long been recognised as one of Shakespeare’s first experiments with a complex tragic hero and a character who is a virtuoso actor, playing several roles in one. It is perhaps no coincidence that the other roles for which Burbage was to become most famous are some of Shakespeare’s later, multifaceted tragic heroes, namely, Hamlet, Othello and King Lear—roles which Shakespeare created for Burbage and which may have been partly inspired by Burbage’s Protean versatility and talent for convincing impersonation.

As contemporary accounts make clear, Burbage was specially admired for his life-like performance and his ability to convey a range of emotions—and sudden changes of feeling—visibly and convincingly in his words, actions and looks. Thus, Thomas Bancroft perhaps thinking of roles such as Romeo, recalls Burbage as a performer who:

… when his part

He acted, sent each passion to his heart;

Would languish in a scene of love; then look

Pallid for fear, but when revenge he took,

Recall his bloud; when enemies were nigh,

Grow big with wrath, and make his buttons fly.

In similar fashion, Restoration commentator Richard Flecknoe not only praised Burbage as ‘an excellent Orator’ who animated ‘his words with speaking, and Speech with action’, but celebrated him for his expressive silences and his ability to ‘paint’ emotions with his looks, observing that he never fell ‘in his Part’ even ‘when he had done speaking; but with his looks and gesture’ maintained ‘it still unto the heighth’.

Contemporary playwright, John Fletcher, likewise, alludes to Burbage’s expressive looks and his compelling portrayal of powerful emotions, in his 1619 elegy for the actor. Implicitly recalling the graveyard scene from Hamlet, Fletcher describes how

oft haue I seene him leape into a graue

suiting the person wch he seemd to haue

of a sad lover, wth soe true an eye

that there (I would haue sworne) he ment to die.

Simon Forman’s rare eyewitness report of a performance of Macbeth at the Globe Theatre in 1610 implicitly offer further evidence of Burbage’s talent for portraying the emotions of Shakespeare’s tragic protagonists vividly. Although Burbage is not explicitly named as Macbeth’s performer, the contextual evidence suggests that the part was first performed by him. Just as Fletcher draws attention to Burbage’s skill in playing the part of an ardent lover, so Forman’s account echoes Bancroft’s in testifying to Burbage’s ability to embody fear and anger, describing how, during the banquet scene the spectacle of Banquo’s ghost appearing to Macbeth ‘fronted him so, that he fell into a great passion of fear and fury’.

Contemporary reports, likewise, point to Burbage’s talent for convincing death scenes—a key and culminating moment in his portrayal of each of Shakespeare’s tragic heroes. In Fletcher’s elegy, for example, his allusion to Hamlet’s graveyard scene is followed by praise for Burbage’s vivid impersonation of dying and its powerful impact on audiences:

Oft haue I sene him play his part in iest

soe liuely, that spectators & the rest

of his sad crew, whilst he but seem’d to bleed

amazed, thought, he then had died indeed (f. 62v).

Such was contemporaries’ admiration for Burbage’s acting, especially in Shakespeare’s plays, that his death in 1619 was more volubly mourned than that of Shakespeare himself three years earlier, prompting multiple poetic tributes celebrating the actor’s artistic talent.

In the Romantic era and since Shakespeare’s admirers have often emphasised the playwright’s status as a lone, original genius, but more recent research on the early modern theatre world has made clear the extent to which the Shakespearean stage was a collaborative one in which various factors shaped the plays created by playwrights such as Shakespeare, including the acting companies and actors for whom they wrote.

In the case of Shakespeare and Burbage, the collaboration of writer and actor appears to have been an especially rich one, their mutual talents serving to inspire each other to a greatness and gift for complex, life-like characterisation not known before on the English stage the fruits of which we still get to enjoy, thanks to the preservation of Shakespeare’s plays, and Burbage’s roles within them, in the early quarto editions and the First Folio.

Siobhan Keenan

5th September 2022