Dominic Dromgoole

In the several varied spaces I have come into contact with a First Folio, there has always been a disjunct between the sense of awe on approach, and the unprepossessing nature of the artefact itself. Whether in the sanctified sophistication of a Christie’s showroom with the recent very fine Mills College copy, which sold for $10 million; in the Fort Knox vault several floors below the Folger library in Washington DC, where 82 are shelved against a single wall; in a collector’s room of dreams in a New York brownstone, or in a plain and modest reading room in the Guildhall library – wherever I have leafed through its pages, there has always been a blend of wonder at its marvels and disappointment at its plain-ness. The greatest treasure trove of imagination, observation, stories and human insights humankind has assembled in a single volume, it is finally just a book. And a badly printed one at that.

It may be banal to drop from the Folio to an Indiana Jones film, but there is an apposite moment at the end of The Last Crusade. After much questing, the hero has to choose which of a selection of goblets and cups is the Holy Grail. Unlike the villain who went for the gaudiest and paid the price, Indiana walks past the highly fashioned and jewel-encrusted containers, and goes for the plain painted clay cup. Since its powers are so mighty, its physical presence only has to be modest. Each Folio I have met has been as unassuming, about 13 x 9 inches and about 3 inches thick. On each occasion, an inner hunger for corniness has anticipated it might shine or glow, or that some literary radioactivity would pour from it. It never has. Breath is held on opening it, then exhaled on remembering it is just a book.

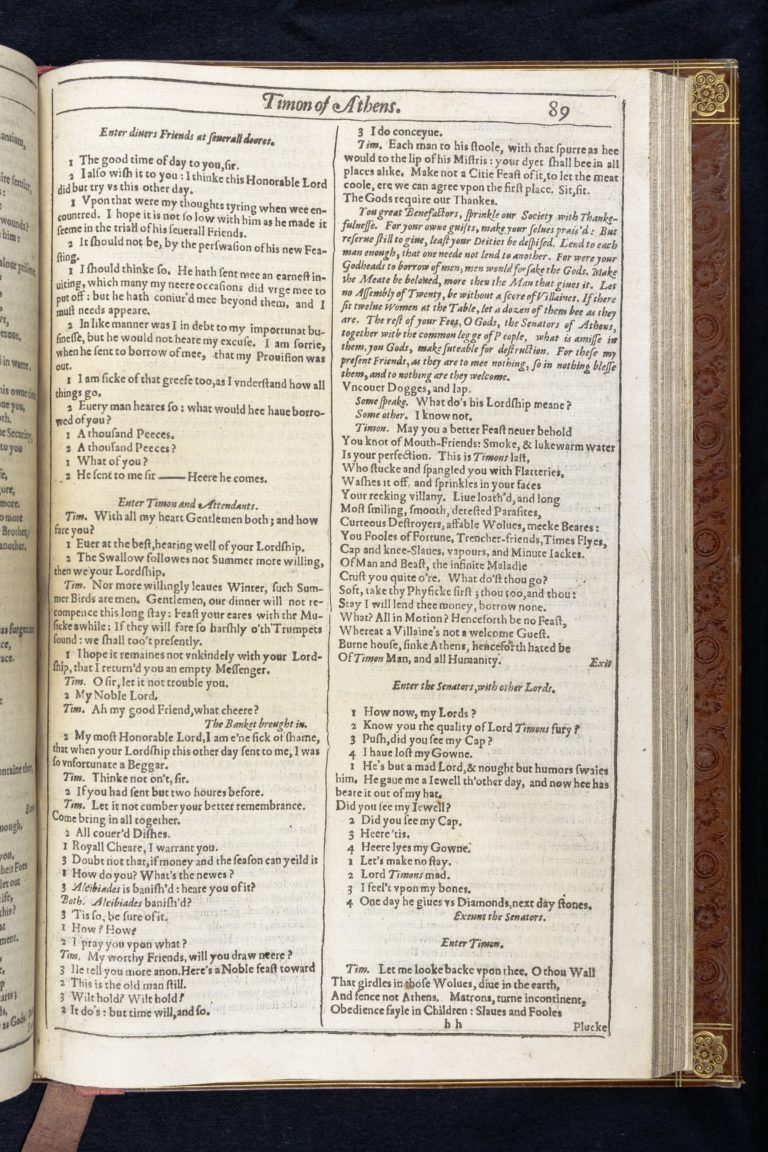

The front few pages are a cloudy grey, the rest have a dull creamy texture, across which the text is laid out plainly, two columns to a page. The almost fastidiously dull Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare seems to memorialise a dedicated middle manager rather than a blossoming genius. There is no flash or fancy illumination, just a few discreet neoclassical decorations, in which a little fat Buddha figure is assailed by two griffins wrapped in coiling foliage. Beside Ben Jonson’s Folio, a polished work of printing, supervised by the author himself and published in 1616, Shakespeare’s First Folio looks hopelessly amateur. But then so do Bottom, Flute, Starveling et al, and yet somehow those amateurs comprise a performance of Pyramus and Thisbe which is the defining glory of the English Stage.

The text is loose; there is a definite sense of it being rushed. Characters names come and go, sometimes alternating with the names of the actors playing them; often characters are announced at the beginning of scenes, and then disappear, making no contribution to what occurs. Sometimes, as in Timon of Athens, they aren’t named at all, and whoever is speaking is denoted with nothing more than a bare 1, 2, 3 or 4. (Which must have been a hard sell to some of the company – ‘Tonight, Mr Armin, you will be playing 4.’) Some of the stage directions look as if the author is reminding himself of what he’s supposed to be doing with a scene.

There is throughout the sense of a first draft, and the wonderfully scrappy, open-to-chance nature of Elizabethan playwriting. Shakespeare’s company turned over plays at a phenomenal rate and you get an impression of the pace at which they used to write. There is none of the stultifying, self-enclosed, desperate need for polish that inhibits so much writing these days; nor is there any nonsense about working out in advance what a play is about and articulating that message. This is writing Elizabethan style – on the hoof, raw, fast, shifting and alive.

It is of course a blueprint for something else – a series of performances – rather than an artefact, and begs little admiration for itself. It is asking to be transformed, to be spoken and acted; it does not want to sit on the page. It is amazing how readable it is. Something so old should be impenetrable, but the Folio is easier to read and quicker to access than any reproduction. The words dance and pulse and breathe within their light scatter across the page. Encountering the sheer quantity of life within it, its sheen of banality drops away and one is thrilled afresh at coming into contact with something so authentic, so close to the source, so in touch with the original magic.

Around 25 years ago, on a summer’s night, two hours before Beautiful Thing by Jonathan Harvey was due to open at the Bush Theatre, I was bent over a complex jigsaw of sheets of paper, sweating from frequent trips to an over-heating photocopier. It was the middle of a recession, and not a great moment for theatre publishing, never a runaway trade at the best of times. We had tried to secure a publisher for Jonathan’s play, but without success – no one thought it would sell. Never happy to take no for an answer, we decided to launch Bush publishing. This grand title turned out to mean me and my equally sweaty assistant trying to master the mathematics of pagination.

Beautiful Thing, our first volume, wasn’t a thing of beauty. Its pages were unevenly laid out, with the occasional one sticking out at an alarming angle; its cover was brightly coloured thick card, which refused to fold over and kept bouncing up; the design on the front was crude. But the play was inside, the volume had an official-looking ISBN on the back, and we beamed with childish pride. The show was a whopping hit, and our first few print runs sold out, before heavier hitters stepped in and bought up the rights. Thousands and thousands of copies were sold.

Some of that determination to get something done is exemplified by the Folio. It looks as if it was put together by actors, rather than by publishers. At least five different compositors worked on it, all of them carefree in their attitude to verse, spelling and sense. If they were getting to the bottom of a page and still had too many lines to get in, they simply lengthened the lines and squeezed them in any old how, creating car crashes of blank verse. If they had too much space, they minimised the words in each line, and edged Shakespeare towards e e cummings. It is joyously slapdash, and has kept academics, brows furrowed, debating ever since.

It is not just the roughness that betrays the work of actors – it is also the enthusiasm. This shines out of the dedication at the beginning, and the commendatory verses, too, commissioned from Jonson among others. Theatre folk are frequently accused of gushing, and a certain amount of all-round flattery was a feature of any publication of the time, but the warmth of these verses, and the pride of those involved, stands out. They show a touching combination of self-aggrandisement and affection for a friend and colleague.

The lesson of the Folio followed through to all our work at the Globe. Our ambition was to present the plays as if they were new. The Folio was an indispensable aid in locating that freshness. Contingent on the crowd and the weather and the mood of the moment, the Globe aimed to be as in the here and now as we could. We wanted to avoid the manufactured and blow-dried composition which bedevilled other representations. Gustav Mahler said that, ‘Tradition is tending the flame, not worshipping the ashes’. In its very modesty and plainness, the Folio eschews falsity, pomp and grandiosity. It helps to keep us enthusiastic, and to keep the flame steady.

Dominic Dromgoole

18th January 2021