We rightly celebrate the 1623 First Folio for preserving the canon of thirty-six of Shakespeare’s plays, providing us for the first time with texts of The Tempest and Macbeth and sixteen other plays that had never been printed, as far as we know. So we have only one ‘authoritative’ text of each of these eighteen plays and cannot compare them with other versions of the plays printed during or shortly after Shakespeare’s lifetime.

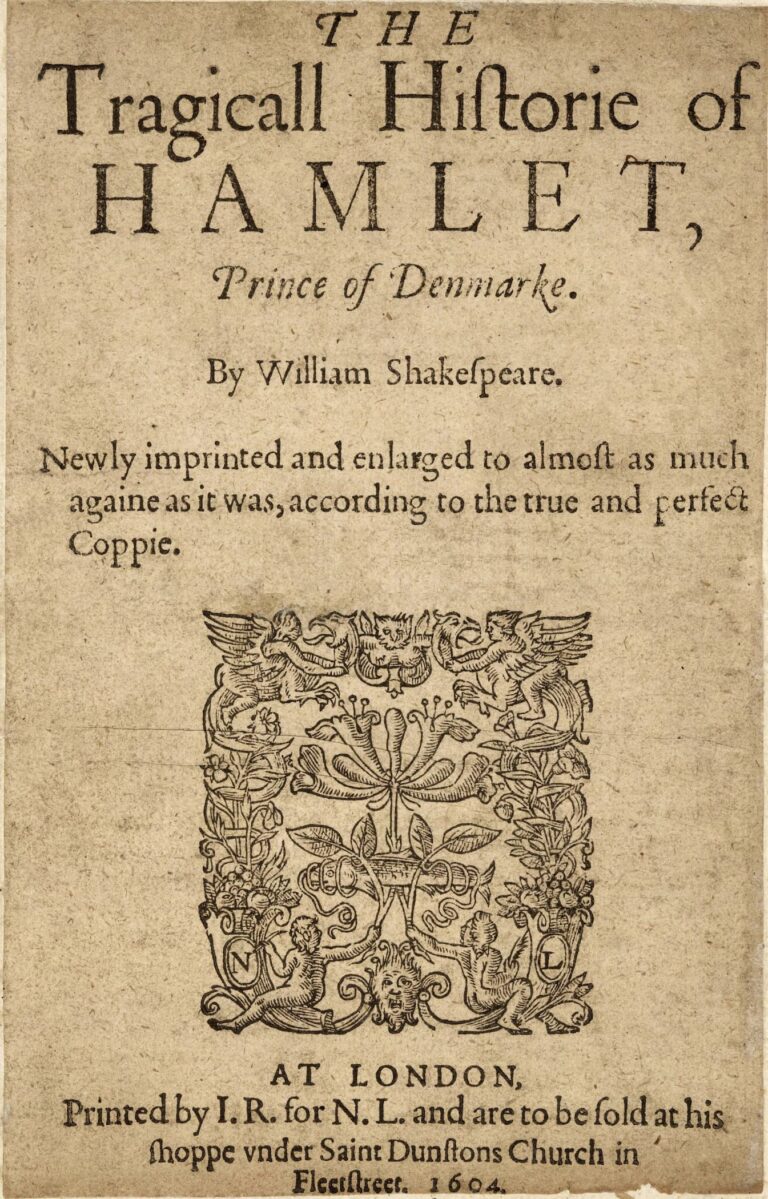

However half of the plays in the Folio had been published previously in Quarto format. For a Quarto, the printer would use a Folio-sized piece of paper to create eight pages of text—four on each side (to understand this format, fold a piece of paper twice–once horizontally and once vertically–cut open the uncut pages and number all the pages in sequence). When put into printing frames, the compositor could then set the type of four pages on each side of the sheet, with, for example, pages 1, 4, 5 and 8 on one side of the sheet and pages 2, 3, 6 and 7 on the other side This required much more complicated typesetting than for a Folio (fold a piece of paper once, numbering the pages 1-4, with pages 1 and 4 on one side and 2 and 3 on the other). The Quarto compositors would have to ‘cast off’ lines of his source text to anticipate which lines would appear on page 4, 5 and 8 while printing page 1 before turning over his frame to print pages 2,3 6 and 7. Thus for a Quarto, usually sold unbound and cheaply, almost as a forerunner of a modern paperback, there was a higher rate of printing error than for a Folio, printed with page 1 and 4 on one side and 2 and 3 on the other. However, the First Folio format didn’t make for easier reading than the Quartos, for the Folio text of the plays was set in two columns per page to save space, meaning that a reader had to read down one column then go back to the top of the page to read down the next column. The Quartos were set as we are used to seeing modern texts printed with, in effect, one column of the text before a reader turned the page. Thus, for all its fabulousness as a grand volume, and much heavier weight, the Folio makes for more difficult reading and carrying than a lowly Quarto, which could fit into a pocket and be carried. The Folio would sit on a desk; a portable Quarto could go anywhere.

Even if occasionally sloppy or misprinted, the extant Shakespearean plays printed in Quarto form give us us a fantastic opportunity to compare earlier versions with later versions in the Folio, giving us almost certain evidence of text revised, altered, updated or adapted by Shakespeare himself. Unusually for an early modern dramatist, Shakespeare profited from at least three stages of the transmission of each play he wrote: first when he sold it to his acting company (the Lord Chamberlain’s, later the King’s Men), second from a share of the box office receipts for its performances (both as an acting company shareholder and a shareholder both in the Globe and Blackfriars playhouses) and again from a share when the play was sold to a printer (copyright did not exist, and once sold, a text belonged to the printer, although Shakespeare seemed to have had mutually beneficial business relationships with his usual printers).

Revision was a common practice among Shakespeare’s colleagues and contemporaries, including Ben Jonson, Thomas Middleton, Thomas Heywood, and many others. Whenever possible, the original authors were usually paid to revise an existing play. Philip Henslowe’s famous ‘Diary’, or account book, recording payments to dramatists for ‘addicians’, ‘mending’ and ‘altering’, provides ample evidence of this practice (see the digitised ‘Diary’ here: https://henslowe-alleyn.org.uk/catalogue/mss-7/). Henslowe repeatedly made clear that other company personnel, including scribes, bookkeepers, company managers, and actors were not employed to make revisions in the manuscripts of plays owned by the acting companies he financed.

There is every reason to believe that, given Shakespeare’s investments in the various stages of performance and printing of his plays, he did the revisions himself. When Hamlet instructs the acting company visiting Elsinore, ‘Let those that play your clowns speak no more than is set down for them’, we hear a proprietary Shakespeare trying to protect his lines exactly as he wrote them. If he is not loud enough here, we can read his friend and colleague Ben Jonson’s many angry commentaries in his play prefaces or elsewhere on the non-authorial alterations to his lines. In fact, he forces the audience to agree to a contract to accept his authority in the Induction to his 1614 play Bartholomew Fair.

Those of us who study the full transmission of early modern English plays usually begin by figuring out what served as ‘printers’ copy’ for each edition. The usual sources could be: ‘foul papers’ (a common term of the age, used by writers, scribes, copy-houses, and even customers paying for copies, including the great actor Edward Alleyn), which was the author’s first draft; a ‘fair copy’, which was a later copy made by the author or a scribe; a ‘prompt-book’, or a marked-up manuscript used to cue actors; or even a later marked-up copy of an already printed Quarto, among other kinds of texts. Shakespeare seemed to have preferred the authority of foul papers, for he mocked the extra fine-tuning of fair copies at least once: in Love’s Labour’s Lost, he has Katharine complain that Biron’s heavily practiced and calligraphic, and thus insincere, love letter to her is as ‘fair as a text B in a copy-book’.

Authorial revision, including the type of additions, mending and altering recorded by Henslowe, could occur at any stage of a play’s transmission and could include simple updating, for example, changing references to the Queen (Elizabeth I) in the 1602 Quarto 1 of The Merry Wives of Windsor to the King (James I) in the Folio, or adjusting for later audience taste, or the removal of oaths after the Act to Restrain Abuses of Players of 1606. But sometimes the revision was apparently due to Shakespeare’s changing artistic vision. He altered, added or deleted characters, plots, and structures. He also responded to the demands of censorship and changes in acting company, venue or audience, as well as the political climate. These revisions are traceable by comparing Quarto and Folio texts particularly of The Merry Wives of Windsor, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Titus Andronicus, Love’s Labour’s Lost, Romeo and Juliet, the Henry IV plays and the Henry VI plays, Othello, Hamlet and King Lear. But authorial revision can also be found within single edition plays, for example in the Folio texts of Macbeth and Julius Caesar. It’s no surprise that his most extensive revision came in his two greatest plays, the tragedies of Hamlet and King Lear, the plays on which he probably knew his reputation would rest.